Understanding Thailand’s irredentist nationalism via its historiography

Thailand’s ‘lost territories’ narrative serves to unite the nation against external threats while discrediting internal enemies as traitors. Montage

In The Lost Territories: Thailand’s History of National Humiliation (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2015), author Shane Strate examines Thailand’s irredentist nationalism through the lens of Thai historiography. Drawing on extensive Thai archival sources, his book reveals how successive Thai regimes have invoked “national pride” in escaping colonisation and yet contradictorily claimed “victimhood” over “territorial losses” to Laos and Cambodia, forging a national imaginary of a metaphorically mutilated body requiring restoration—one that continues to fuel active irredentist nationalism in contemporary Thailand.

Thailand’s contradictory meta-narratives Ironically, the two contradictory meta-narratives coexist in Thailand’s official historiography: “Siam was never colonised” (the chosen myth) and “national humiliation” (the chosen trauma). The first narrative serves as the foundation of political legitimacy for the monarchy and its conservative allies. Thai royalist-historians portray Kings Mongkut (Rama IV, who reigned from 1851 to 1868) and Chulalongkorn (Rama V, 1868 to 1910) as heroes who initiated modernisation and integration into global capitalism, eliminating any pretext for colonisation. This forms the foundation of Thailand’s subsequent “bamboo diplomacy”—tactical flexibility that helped Thailand emerge unscathed from WWII.

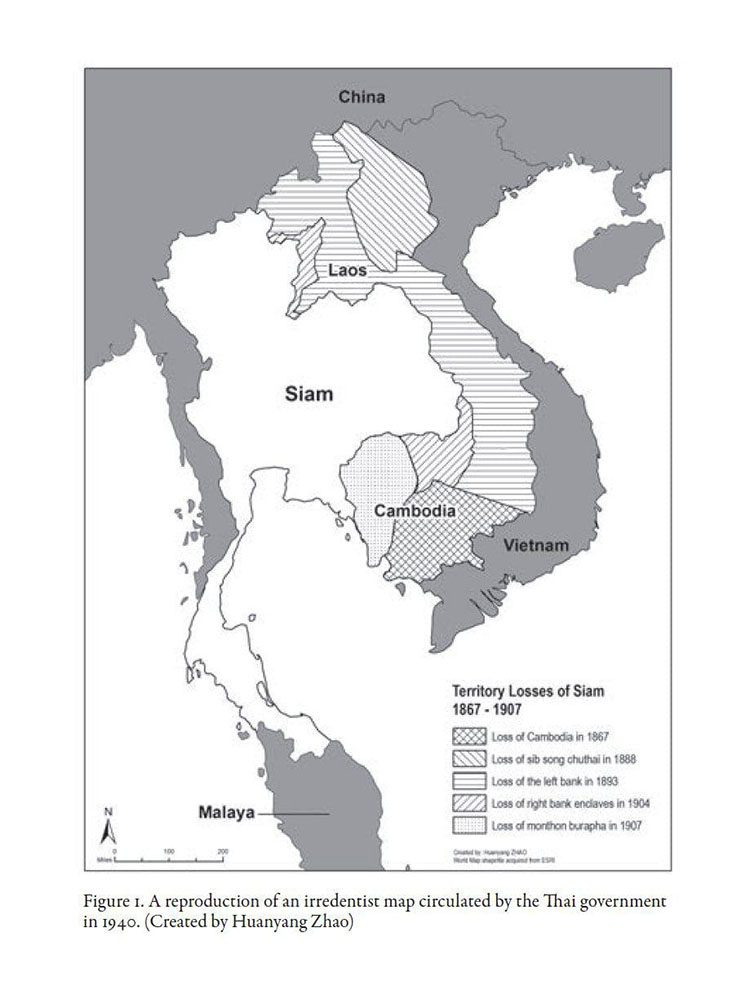

In contrast, the second narrative laments “territorial losses” to colonial powers, particularly the French colonists. The Franco-Siamese crisis of 1893 when France sent gunboats toward Bangkok and seized territories that became Laos is remembered as the symbol of Thai national humiliation. Subsequent treaties with France in 1904 and 1907 over the boundary between the Kingdom of Siam and the French Indochina, combined with the French occupation of Chanthaburi and Trat, transformed a momentary diplomatic defeat into prolonged national trauma.

Thai discourse of ‘national humiliation’

The memory of Thailand’s “lost territories” due to Western colonial powers was later constructed and perpetuated by the Thai military regimes and cadre-historians as colonial aggression on the Thai nation. Emerging after the 1932 military coup, Phibun’s regime reframed 1890–1910 as a period of “unequal treaties” and discursively represented the “territorial losses” as national humiliation, which has legitimised the military as the guardian of national sovereignty.

Recognising that the monarchy remains a strong source of legitimacy, the post-1932 military regimes blamed the monarchical institution for capitulating to imperialism while discursively sparing individual monarchs from criticism. By 1940, the Phibun government had successfully transformed the “lost territories” discourse into an anti-colonial mobilisation tool that legitimised military rule.

Phibun’s regime (1938–1944) used this narrative of “national humiliation” narrative and territorial grievances to justify its irredentism and reconquest policies, with the regime ideologue Wichitww Wathakan leading historical revisionism that framed conquest as recovery of their territorial loss and used history as a tool for post-monarchical legitimacy. The military government distributed colour-coded maps, textbooks, and posters to create durable emotional memory among the Thai population.

The Thai nationalists constructed a fantasised territory by referencing the “historic” borders of Ayutthaya before 1893, incorporating Laos and Cambodia into school curricula and maps as part of Thai territorial heritage through ethno-historical arguments that portrayed Khmer and Lao as “branches” of the Thai people. This creation of an encompassing “Thai race” category erased neighbouring Lao and Khmer identities and justified irredentist ambitions through racial assimilation, establishing a mutilated geo-body that required restoration—a concept anchored in metaphors of lost limbs needing recovery.

Utility of ‘national humiliation’ discourse

Thailand’s “lost territories” narrative serves to unite the nation against external threats (France in the past, Cambodia at present) while discrediting internal enemies as political opponents and traitors. Memory of the “lost territories” becomes a powerful instrument of power that justify authoritarian policies and aggressive military actions against its neighbours. This narrative experienced recurrent reactivation during conflicts, such as the Preah Vihear temple dispute with Cambodia (2008-2011), and was disseminated through media and education to maintain traumatic memory as a tool of political control. The memory remains vivid in official discourse and education, creating latent irredentism that threatens relations with Laos and Cambodia.

Strate draws a conclusion that the “lost territories” narrative functions not as a location but as a symbol commemorating national humiliation, a discourse continually reinterpreted and instrumentalised by later generations of Thai military leaders, politicians, and nationalists to meet their contemporary needs. This narrative continues to serve as a powerful tool to unify the Thai nation against foreign threats and those within Thailand perceived as betraying the country.

The Thai narrative of “lost territories” continues to fuel Thailand’s irredentist nationalism, and its expansionist ambition over the self-proclaimed “lost territory” to Cambodia. Thailand’s insistence on Cambodia’s acceptance of its unilaterally drawn maps in all bilateral negotiation mechanisms is a manifestation of Thailand’s rejection of the Franco-Siamese Convention of 1904 and Treaty of 1907 and a denial of its colonial legacies. Thailand’s preference for bilateralism to international law, including the International Court of Justice or third-party mediation is not difficult to understand. Simply put, a more powerful Thailand can apply military and economic pressure on a much weaker Cambodia to extract territorial concessions in bilateral negotiations.

The author is Advisor to Asian Vision Institute. The views expressed here are his own.

Khmer Times