The Kuala Lumpur Accord: A Test of ASEAN Diplomacy and Superpower Restraint

-Opinion-

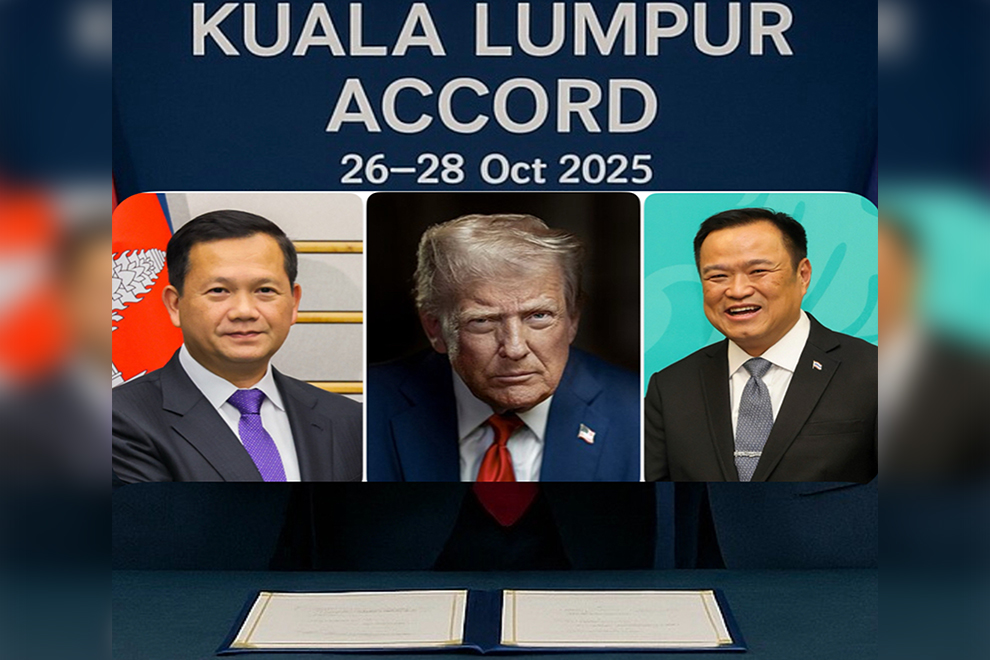

After the bloodiest border flare-up in more than a decade, Cambodia and Thailand are preparing to sign a peace accord during the 2025 ASEAN Summit in Kuala Lumpur, with US President Donald Trump expected to attend. The event promises symbolism and spectacle but in Southeast Asian diplomacy, symbolism rarely guarantees peace. To matter, this accord must rest on verifiable commitments and sustained regional engagement.

The July 28 cease-fire halted five days of clashes that displaced more than 300,000 people and cost Thailand hundreds of millions in economic losses. Malaysia’s leadership as ASEAN chair, backed by US pressure, has brought the two sides to the table. China has also voiced support, calling for restraint and dialogue.

For once, major powers’ interests appear aligned. Washington seeks a diplomatic win; Beijing prefers stability to protect its regional investments; ASEAN wants proof it can still mediate conflicts among its members. The proposed “Kuala Lumpur Accord” would include heavy-weapons withdrawal, land-mine clearance and the gradual reopening of border crossings.

Yet cracks already show. A PMN-2 landmine that wounded Thai troops in July was likely newly laid, an apparent breach of the Ottawa Treaty, which bans anti-personnel mines. Cambodia denies responsibility and accuses Thailand of “psychological warfare” using loudspeakers and drones to intimidate villagers. Meanwhile, Bangkok has postponed Regional Border Committee meetings, citing Phnom Penh’s vague disarmament plan, an ominous sign for implementation.

Domestic politics complicate matters further. Thailand’s government has floated a referendum to revisit border-demarcation agreements, playing to nationalist sentiment. Cambodia’s alignment with China deepens suspicion in Bangkok. Without strict verification, even a signed accord could unravel.

The US-China Dimension: Opportunity and Caution

The evolving Cambodia-Thailand peace initiative unfolds against a broader backdrop of strategic rivalry and uneasy cooperation between the US and China. Both powers, though driven by different motives, are now positioned to shape the success or failure of the Kuala Lumpur Accord. Their combined involvement brings opportunity, but also profound risks.

Trump’s participation lends the process both visibility and volatility. His presence raises the accord’s profile and could add leverage; earlier, his threat to delay trade negotiations reportedly helped pressure both Phnom Penh and Bangkok into accepting the July cease-fire. By investing personal political capital, Trump has made himself an accountability anchor; a visible guarantor of commitment.

Yet his brand of diplomacy often prizes spectacle over structure. Trump’s self-declared record of “ending eight wars” famously included conflicts that were never fully resolved.

The danger is that Kuala Lumpur delivers a photo-op and headlines without enforcement. Washington’s attention span is short; without steady funding for monitoring, mine-clearance and reconstruction, the US role may fade once the cameras leave. A peace deal defined by publicity rather than performance could leave ASEAN to manage the fallout alone.

China’s role presents a different, but equally ambivalent, picture. Beijing’s economic influence and close ties with both sides make it indispensable to long-term stability. It can underwrite mine-clearance operations, finance border infrastructure and link stability to growth through its Belt and Road corridors connecting Cambodia and Thailand. A peaceful border aligns neatly with China’s commercial and strategic interests, while its endorsement also reassures ASEAN members that the process is not purely a US-driven agenda.

Yet caution remains warranted. Analysts note that China’s mediation style favours quiet diplomacy over transparent enforcement. If Beijing uses its participation to expand influence such as deepening access to the Ream Naval Base in Cambodia; the accord might stabilise the frontier only to shift regional power dynamics.

For the peace deal to endure, Washington and Beijing must converge on verification rather than compete for credit. The US can supply political visibility, diplomatic pressure and technical expertise in de-mining and border monitoring, while China can sustain economic and infrastructural recovery. Coordinated transparency such as shared data on weapons withdrawal and mine-clearance would demonstrate that both great powers are capable of cooperation in the service of peace.

If instead they treat the accord as a stage for influence, its stability will prove as fragile as the cease-fires that came before it.

Why This Deal Matters

If implemented, the accord could transform the border frontier from a militarised fault line into a trade corridor. A functioning joint mine-action task force, verifiable disarmament schedules and transparent monitoring would reduce accidental flare-ups and rebuild trust. Cross-border markets could reopen, restoring livelihoods and giving communities a direct stake in peace.

But if the deal lacks deadlines, maps or enforcement, it will quickly join the list of Southeast Asia’s unimplemented truces: celebrated one week, forgotten the next. Each delay or unverifiable claim of progress will invite renewed skirmishes.

Therefore, the durability of the Cambodia-Thailand peace accord ultimately depends on collective ownership rather than individual political triumphs. For the agreement to endure, each key actor, regional, bilateral and external, must shoulder a distinct yet complementary role in ensuring compliance and transparency.

For Cambodia and Thailand, the foundation of trust must begin with practical steps such as exchanging clear border maps, publishing withdrawal timetables and empowering liaison officers at field level to respond swiftly to incidents or misunderstandings. Transparent coordination between the two armies and local authorities would prevent minor border disputes from escalating into renewed hostilities.

Within ASEAN, Malaysia as the current chair should take the lead in establishing a joint monitoring mechanism, ensuring that weekly compliance reports are publicly released. These updates would demonstrate progress, expose violations and reinforce ASEAN’s credibility as a regional peace facilitator rather than a passive observer.

The US can complement these efforts by linking post-summit assistance such as support for mine-clearance, humanitarian rehabilitation and intelligence-sharing to verified compliance milestones. Conditional engagement would give the accord an external accountability structure, ensuring that pledges translate into measurable results rather than remaining ceremonial gestures.

Meanwhile, China’s role must focus on reinforcing peace through economic and technical support, not geopolitical leverage. By funding mine-clearance operations, investing in border infrastructure and refraining from attaching strategic conditions such as security access or exclusive contracts; Beijing can demonstrate its commitment to regional stability rather than dominance.

Only through this layered cooperation, where ASEAN sets the rules, the US enforces accountability, China supplies pragmatic support and the two signatories act in good faith, can the peace deal balance Trump’s publicity-driven diplomacy with China’s cautious pragmatism. The success of the Kuala Lumpur Accord will not rest on a single handshake but on sustained, shared responsibility across borders and capitals.

The Bottom Line

The coming summit in Kuala Lumpur will likely deliver spectacle, flags, cameras and signatures; but peace will be measured not by the stage but by the field, by kilometres of cleared minefields, reopened border gates and days without gunfire. If the accord embeds maps, milestones and monitoring, it could become a model of regional problem-solving.

If it delivers only rhetoric, it will be remembered as another performance: Trump’s theatre meeting China’s calculus, with the people on the once again caught in between.

Seng Vanly is a Phnom Penh-based geopolitical analyst. The views and opinions expressed are his own.

-The Phnom Penh Post-