Cultural Heritage Under Fire: Why Thai Military Commanders Must be Held Accountable for War Crimes

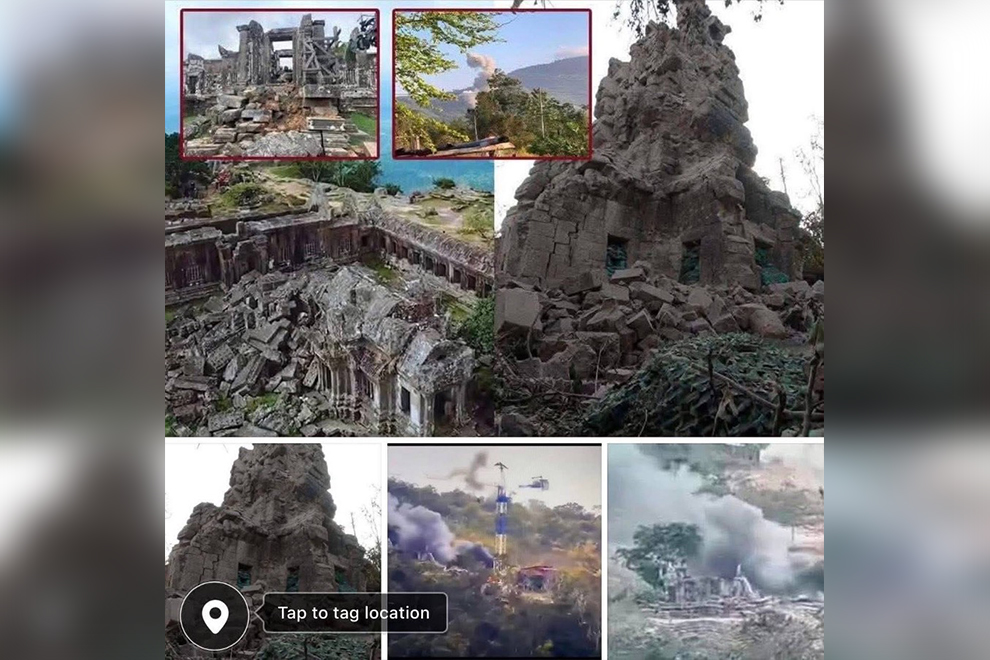

[Extensive damage has been recorded at cultural sites near the Thai border, as artillery and airstrikes continue to hit Cambodia. Supplied]

[Extensive damage has been recorded at cultural sites near the Thai border, as artillery and airstrikes continue to hit Cambodia. Supplied]

[Opinion] I first walked among the Temples of Preah Vihear, Ta Krabei and Ta Mone in the aftermath of the July 2008 hostilities. The air was still — silent not from abandonment but from endurance. These were stones that had outlived kingdoms and conflicts, standing as steadfast guardians of memory, art, faith and civilisation. To see those same protected temples now struck by heavy weapons is not merely to register a breach of law; it is to feel a wound cut into the heart of Cambodia and into the moral fabric of humanity itself. To wound these temples is, in truth, to wound humanity.

Such scenes raise questions that law alone cannot fully answer. If Thailand truly believes these temples belong to it, where is the reverence owed to what it claims as its own heritage? If they are regarded as sacred, why are they treated as expendable? And if control could not be secured, why was destruction chosen instead? Cultural heritage demands stewardship, not erasure; guardianship is not asserted through bombardment.

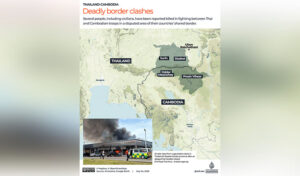

In recent days, Thai armed forces have carried out artillery and air strikes in and around internationally protected cultural sites, including Ta Krabei and the Temple of Preah Vihear. These attacks occurred within recognised heritage and conservation areas governed by international legal protections. Rather than denying the strikes, the Thai Army has sought to justify them by asserting that Cambodia used ancient sites as military bases, thereby forfeiting protection under the 1954 Hague Convention.

In my legal assessment, this claim is unsupported by evidence and inconsistent with international law. It reflects no established military reality. Rather, it appears constructed after the fact to rationalise destruction already inflicted.

No credible proof has been produced to demonstrate that these protected sites were ever militarised. There were no weapons, firing positions, command posts or military installations capable of transforming cultural heritage into lawful military objectives. Under international humanitarian law, allegations of military use must be established by evidence, not inferred by convenience.

UNESCO’s statement of 10 December 2025 reinforces this conclusion. While expressing concern about hostilities in the vicinity of heritage sites, it made no reference — explicit or implied — to any Cambodian military use of protected temples. Had such use occurred, UNESCO would have been under a professional and institutional obligation to record it. Its silence is therefore neither incidental nor neutral; it is legally and evidentially significant.

International law does not permit cultural protection to be withdrawn by assertion alone. The Hague Convention establishes a deliberately high threshold for any suspension of protection. A so-called “temporary loss of protection” may arise only where strict and cumulative conditions are met: clearly established military use, the absence of feasible alternatives and the issuance of effective advance warnings. These safeguards exist precisely to prevent cultural heritage from being reclassified as a military target by expediency.

None of these conditions appears to have been satisfied. There is no indication of prior verification, no evidence that warnings were issued and no record of attempts to pursue lawful alternatives such as UNESCO verification mechanisms, confidence-building measures or regional de-escalation channels through ASEAN. Force was applied first; legal justification followed.

This sequence matters. International humanitarian law is not an afterthought to be consulted once damage has occurred. It is designed to restrain power at the very moment restraint is hardest. When its safeguards are bypassed, the harm extends beyond bricks and mortar, setting a precedent that weakens the protection of cultural heritage everywhere.

The legal consequences are grave. Intentional attacks against protected cultural heritage may constitute war crimes. The International Criminal Court’s judgment in the Prosecutor v. Al Mahdi case confirmed that the destruction of cultural property is not a symbolic or secondary offence, but a serious violation of international law. Crucially, the Court affirmed that individual criminal responsibility may attach to military commanders who order such attacks, facilitate them or fail to prevent them when they have the capacity to do so.

Assertions of military necessity or self-defence cannot displace these principles where their factual foundation is absent. Necessity is not a rhetorical label; it is a legal test. When invoked without proof, it loses both legal credibility and moral force.

The implications extend far beyond Cambodia and Thailand. If cultural heritage can be stripped of protection through unsubstantiated claims made after the event, the protective regime painstakingly constructed in the aftermath of the Second World War is weakened. The Hague Convention was born from the recognition that when civilisation’s monuments fall, something irreparable is lost—not only to one nation, but to humanity as a whole.

The conclusion is unavoidable. The legal narrative advanced by Thailand is untenable. Cultural heritage protection is not optional, nor can it be suspended by allegation alone. Thailand must cease all attacks against protected cultural sites and comply in good faith with the obligations it invokes.

For Cambodia, this is not merely a legal dispute or a diplomatic disagreement. It is about safeguarding a patrimony entrusted to us by history and owed to future generations. Having once stood among those temples in the uneasy calm after war, I know what is at stake. The destruction of cultural heritage — and the distortion of the law designed to protect it — must not, and cannot, go unanswered.

Dara In is permanent representative of Cambodia to the UN Office and other International Organisations in Geneva. The views and opinions expressed are his own.

-The Phnom Penh Post-