Historical Truth and Compelling Narrative As Strategic Appeal and Confrontation

-Opinion-

Nhek Bun Chhay is a former general and a living witness. His recent statement on Cambodia-Thailand border markers and his own experience reveals historical truths and forms a compelling narrative as it pertains to names of other witnesses, exact locations, historical events and dates.

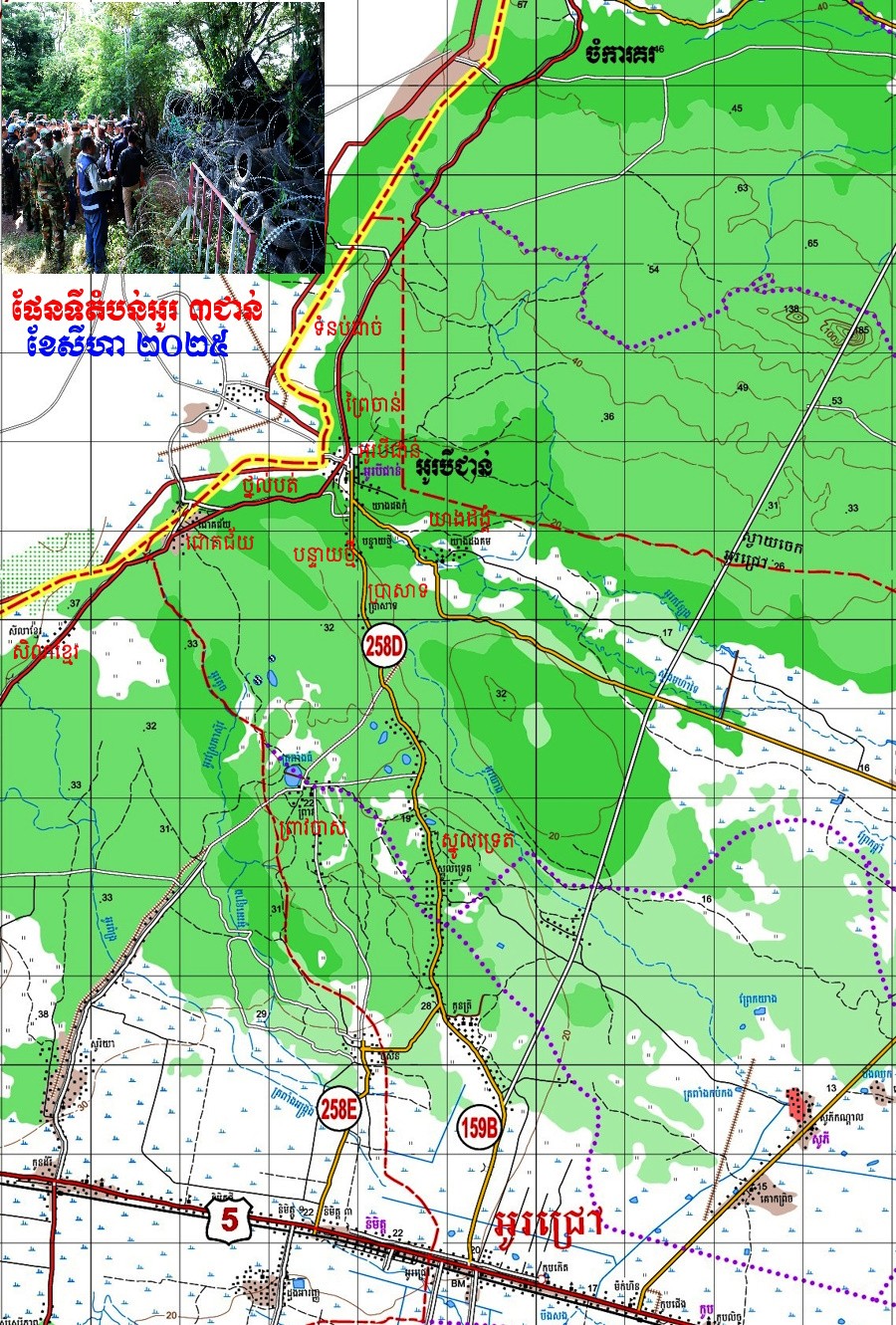

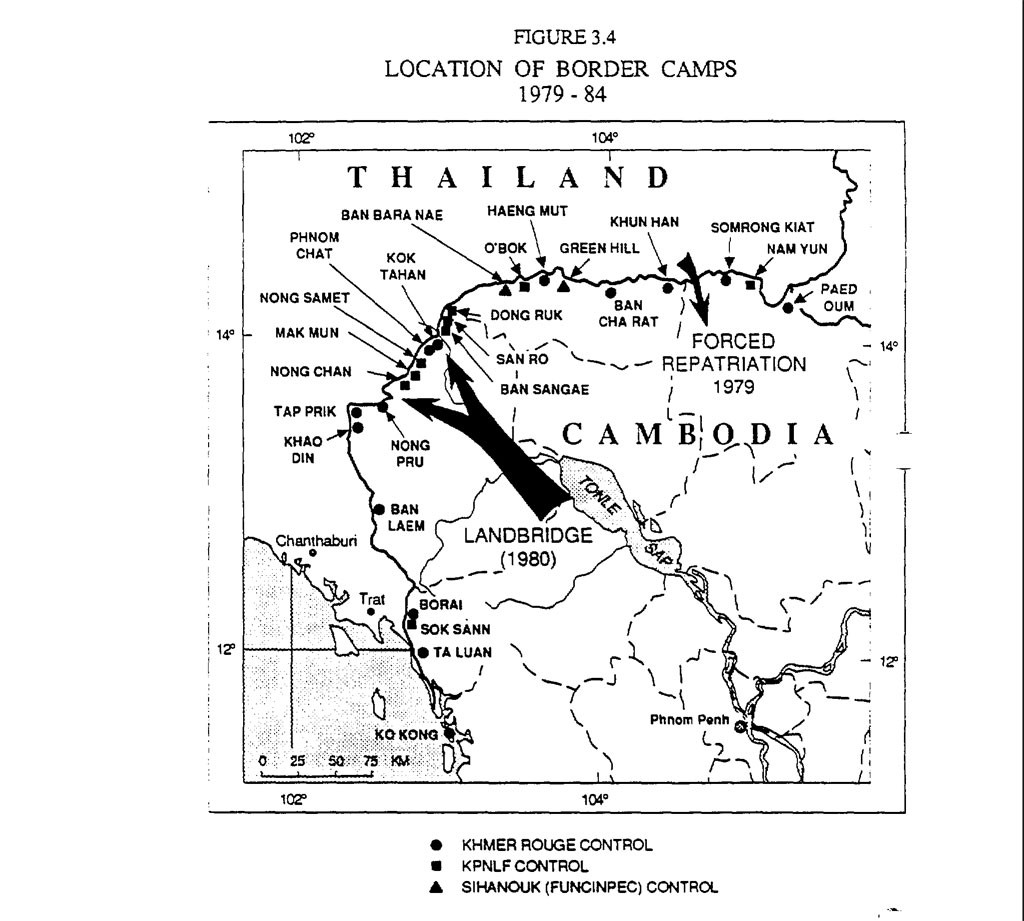

His narrative of the abovementioned corroborate other eyewitness accounts and historical documents, including ones about Prey Chan and Chok Chey villages of O’Bei Choan commune, O’Chrov district, Banteay Meanchey province, which are on the location of a former Nong Chan camp, a recent contested border area between Cambodia and Thailand.

How can this historical truth and compelling narrative be used to strategically confront the the 60-day ultimatum which is due on October 10 and find justice for Cambodia?

This article will discuss the geographical locations in relation to border markers that people witnessed in 1979 and the early 1980s and the relocation of the old Nong Chan Camp to the new one, based on the general’s statement and other testimonies.

This discussion will shed light on the contested areas. It suggests that his statement could challenge and overcome unlawful notices by the Thai military and government. It will help Cambodian people understand the own geography of the border areas and encourage other eyewitnesses to come forward and speak.

Born in Battambang in 1956, and immersed in military and political life along the Cambodia-Thailand border, General Nhek Bun Chhay’s knowledge of the area is crucial. He spent most of his life in the jungle, establishing Cambodian national liberation bases.[1] He knew several Thai generals and soldiers, including then lieutenant colonel Prayuth Chan-O-Cha, who was stationed near the bases he oversaw in 1979 and 1983.

The testimonies below, collected by DC-Cam between August and October 2025, correspondence with Nhek Bun Chhay’s statement and provide further details on the geographical locations.

1) Nong Samet Camp

“On May 5, 1979, Mr. Kong Sileah and I led a military force of 300 men to establish a National Liberation base in front of the Thai village of Nong Samet, located west of Sdok Kak Temple, near Border Marker No. 42. This base was known as the “New Camp,” or “Camp 007”, or “Rithisen Camp”.

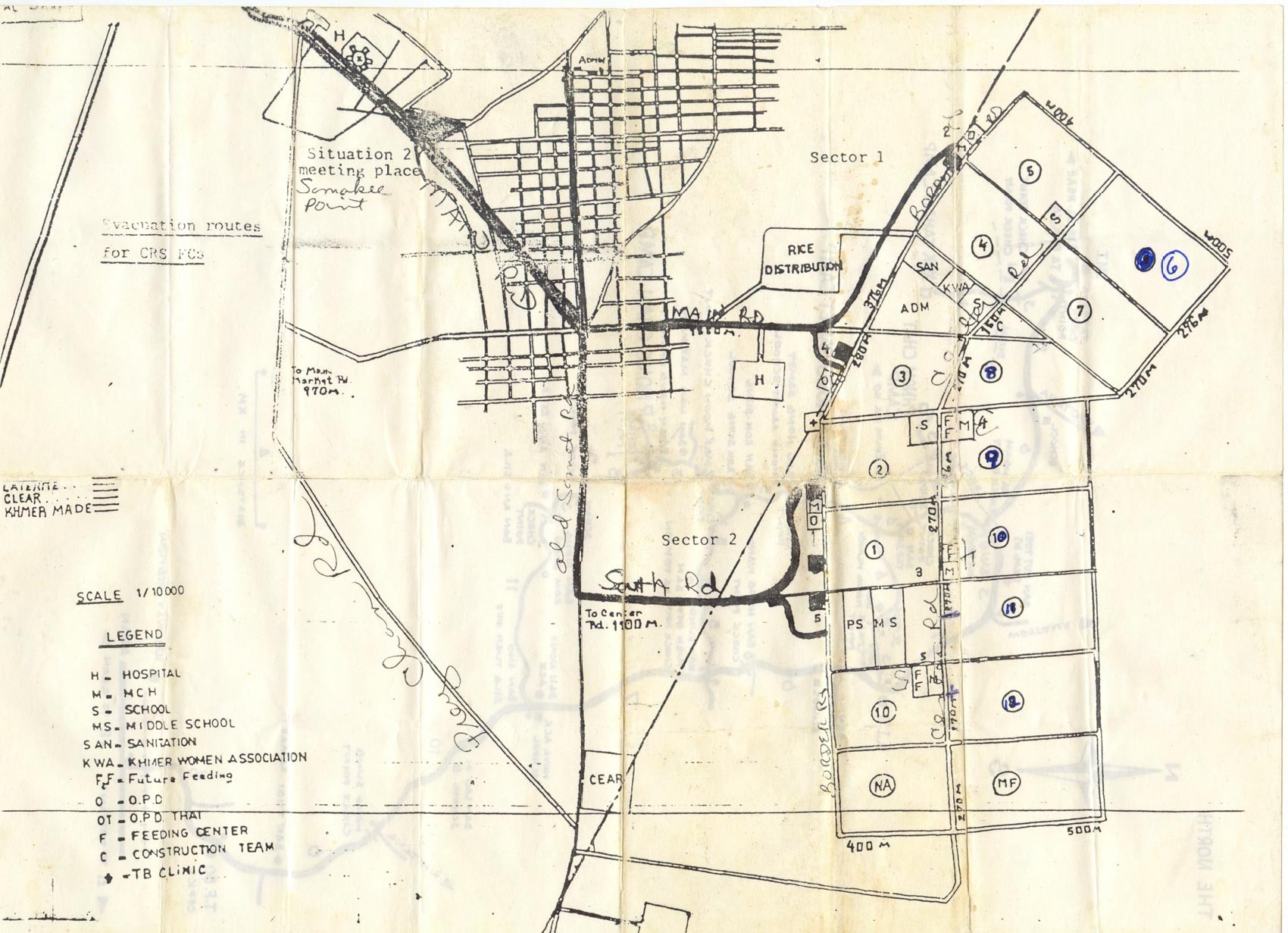

In January 1979, Ros Narith and her family travelled from Battambang town to find her father along the border. She first settled in Nong Samet camp and received a tent and later rice distributed by the UN Border Relief Organization (UNBRO). There were only around 500 families when she arrived. However, the number increased significantly, to between 60,000 and 100,000 people. Nong Samet was called new camp, Camp 007 or Rithisen camp. The camp was originally referred to as Chumrum Thmei (‘New Camp’) to distinguish it from its neighbour and rival Mak Mun Camp, which was also known as Chumrum Chas (‘Old Camp’), overseen by Van Saren.

Nong Samet was later renamed “007” “because of its many intrigues” and in August 1980 was renamed Rithysen.

In late May 1980 Nong Samet was moved to a site adjacent to the Sdok Kak Thom Temple, in an area with poor drainage and landmines left over from a previous conflict. The entire camp was moved again in January 1983 to somewhat higher ground just east of the village of Ban Nong Samet, on land considered to be on the Cambodian side of the border.

This move was precipitated by accusations that Thailand was harbouring anti-communist guerrillas on its territory, thereby aggravating the already complex political situation. While living in the camp, she heard that a Thai guard raped a Cambodian woman refugee outside the camp and later at night the armed Thai soldiers fired on the camp, leaving many casualties.

She has observed that the Thai border was marked by a fence, canal and road. Thai soldiers loved to build roads immediately they claimed land. If we look along the border surrounding Cambodia, Thailand has done this everywhere. She is 100% sure.

Many people who clearly recall this are Cambodians who went to America as refugees. To reach the Khao-I-Dang camp, we had to crawl through the forest through the forest for about a week or two, because the Thai soldiers guarding the fence and watchtowers were ready to shoot anyone crossing into Thai territory.

The fence and watchtowers were on Thai soil. To enter, she had to cross a canal, climb onto the road, descended from the road, and then cross another canal to reach the Khao-I-Dang. It was extremely difficult. As a living witness, she questioned why Thailand continues to encroach upon Cambodian territory and requested all Cambodians to protect their territorial land.

2) Nong Chan Camp

“On August 8, 1979, Kong Sileah and I led a military force of 500 men to establish a National Liberation base in front of the Thai village of Nong Chan. I deployed the troops along the eastern stream of O’Russey Srok, while Kong Silas set up his position at Tuol Prey Preah Phnov, located about 2 kilometres inside Cambodian territory from O’Russey Srok.

The Thai military dug dams and canals along this section of the Cambodia–Thailand border, from Border Marker No. 41 up to Border Marker No. 49. From my own observation, I have seen that there are certain irregularities regarding the border issue in these areas, in which Thailand has encroached upon Cambodia’s territorial integrity. I hope that this issue can be resolved by the Cambodia–Thailand Border Commissions at all levels: The RBC, GBC and JBC, in order to bring justice to Cambodia and our people in the future.”

After Nong Samet camp was destroyed and closed by the Thail Military, Narith moved to Khao-I-Dang camp in Thai Territory. After staying in Khao-I-Dang for a short period of time, she moved to Nong Chan camp. She said that it was 7 kilometres from Nong Chan camp to the Thai border. Nong Chan camp was under multiple attacks by the Vietnamese forces from 1979. Due to the instability, the population moved to another location and a new Nong Chan camp was built further inside Cambodian territory.

According to Long Dany’s interview with Thong Kimleang, 55, resident of Prey Chan village, Nong Chan was located in two different locations within different time period. Old Nong Chan Camp, established in 1979, was located at O-Russey Srok, the former military base of General Nhek Bun Chhay and now at Chamkar Ampov in Chok Chey village near Border Marker No. 45. After the old Nong Chan was destroyed by a Vietnamese attack in January 1983, a new Nong Chan was established in 1983. It was based at Tuol Preah Pnov, former military base of Kong Sileah and is now Prey Chan village, near Border Marker No. 42.

Due to fighting between Cambodian and Thai soldiers, on July 25, 2025, Kimleang left his home in Prey Chan village. On July 26, the Thai military destroyed the Cambodian military base and post in Prey Chan. On July 27, they took them over. On August 12, the Thai soldiers put up razor wire, then moved the people out of their homes on August 13. The Thai military also put razor wire over some houses in Chok Chey village.

Surveillance cameras were set up by the Thai soldiers on August 15 and the soldiers took over part of Chamkar Ampov, which belonged to 20 Cambodian families in Chok Chey village.

Nuon Aun, 62, a resident of Prey Chan village, who was forced to leave her home on August 15, also confirmed that the area is Cambodian territory. She moved to Prey Chan and bought the house and the land in 1990. Her house is 100 metres from the Cambodian military post.

Chok Chey Village: Old Nong Chan Camp (O-Russey Srok and Chamkar Ampov)

Thong Kimleang used to live in Old Nong Chan Camp, now known as Chok Chey village, a former base of General Nhek Bun Chhay. It is about seven kilometres from Prey Chan village. The old Nong Chan has a stream on its west side where he used to play in the water. He and his fellow refugees lived on the south side of the stream. He said the houses were made of sapling and bamboo with roofs of thatch or blue plastic traps. There was also a school, a hospital and other facilities.

Current State of Border Dispute in Prey Chan and Chok Chey Villages

On August 25, the Thai soldiers came to Prey Chan to put up the razor wire, claiming that the area belongs to Thailand. Thailand’s Sa Kaeo provincial administration has ordered the residents of about t00 homes in Prey Chan village, known in Thai as “Nong Ya Kaew,” and villagers in Chouk Chey, referred to as “Nong Chan” in Thai, to leave by October 10.

The Cambodian villagers and authorities rejected the ultimatum. Cambodian authorities have committed to protecting Cambodia citizens at all costs and the unilateral map used by the Thais has never been recognised by Cambodia.

As the deadline to move out nears, the Cambodian authorities reported increased Thai military activity along the border near the two villages, with additional troops and heavy equipment deployed, and repeated inspections of the disputed areas.

On September 18, Thai police fired tear gas and rubber bullets at Cambodians, the most significant escalation since the July 28 ceasefire. The incident injured 28 soldiers and villagers.

Conclusion

The above narrative clearly reveals that the military camps and refugee camps established by Cambodian soldiers in 1979 and the early 1980s were all in Cambodian territory, because Cambodian refugees already explained that if they left the camps and crossed the border, they would be arrested or fined. They each saw the border markers at that time.

After the refugees left the camps inside Cambodian territory at that time, Thailand seized the areas, developed and treated them as Thai territory. Many of the camps were overseen by the Khmer People National Liberation Front (KPNLF) founded by Son Sann, a former prime minister under then Prince Norodom Sihanouk.

Although the demarcation of the land border is complex, the conflict could have been avoided, and the problem solved, if Thailand had not unilaterally moved border markers and violated the rights of innocent Cambodian citizens.

In an interview with Bayon TV, General Nhek Bun Chhay noted that the location of Border Marker 45, near Chok Chey, was resolved by the Cambodian-Thailand Border Commission long ago.

However, Thailand moved the marker about three kilometres into Cambodian territory.

The Cambodian Border Commission discovered this and arranged to move it back to its original location. Despite this, Thailand moved it again and built gravel roads and dug canals into Cambodian territory and gradually considered the locations Thai territory.

If the location of marker 45 was settled, then the issues surrounding markers 42 and 43 would also be resolved because the latter markers are located further in Cambodian territory.

The general’s statement, corroborated by theses testimonies, could be used to refute Thailand’s unlawful attempts to forcibly relocate Cambodian villagers.

More oral testimonies and historical documents are needed, to seek justice and peace for Cambodia.

So Farina is deputy director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam). The view and opinions expressed are her own.

-The Phnom Penh Post-

#CambodiaWantsPeace

#JusticeForCambodia

#Cambodianeedpeace

#TruthFromCambodia

#ThaiLawOnCambodianSovereignty

#ទាហានថៃបានអនុវត្តច្បាប់ថៃនៅលើទឹកដីខ្មែរ