As ‘Board of Peace’ Mooted, a Cambodian Reflects on Kingdom’s Past Neutrality, Descent into War

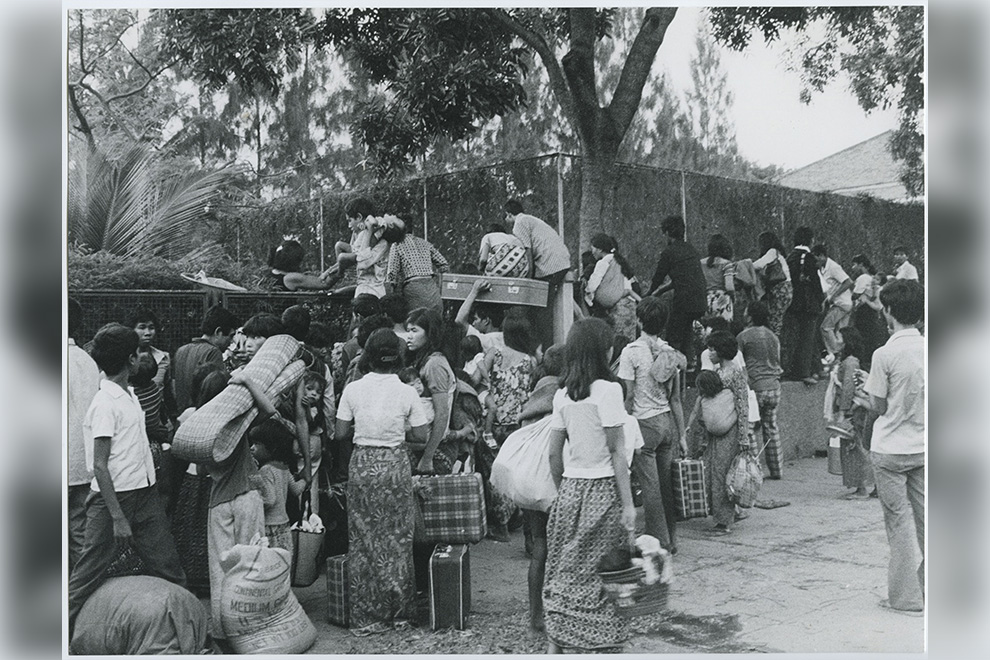

PHOTO: Cambodians take refuge at the French embassy in Phnom Penh in 1975 as the Khmer Rouge capture the capital. The genocidal regime's takeover of the Kingdom was the culmination of decades of outside influence. ICRC..

PHOTO: Cambodians take refuge at the French embassy in Phnom Penh in 1975 as the Khmer Rouge capture the capital. The genocidal regime's takeover of the Kingdom was the culmination of decades of outside influence. ICRC..

#Opinion

At the outset, I wish to make one point absolutely clear: I respect and follow the decisions made by Cambodia’s leadership. The determination of Cambodia’s foreign policy rests solely with the Royal Government, in accordance with national sovereignty, constitutional authority and the country’s long-term interests. The reflections expressed here do not challenge that responsibility. Rather, they arise from historical memory — old wounds that continue to shape how many Cambodians understand international power politics today.

It is within this historical context that I wish to share a personal reflection regarding recent invitations to participate in a so-called “Board of Peace”, an idea raised by the administration of US President Donald Trump.

Cambodia’s descent into civil war and prolonged national tragedy from 1954 through the 1990s was neither accidental nor the result of internal failure alone. It was the consequence of sustained external pressure, regional interference and deliberate destabilisation directed against Cambodia’s independence and neutrality. From the years following independence, through the civil war of 1970–1975, and into prolonged conflicts after 1979, Cambodia paid an extraordinary human price. An estimated 1.7 million Cambodian lives were lost as a direct and indirect result of war, famine, forced labour and political violence.

Following the 1954 Geneva Conference, Cambodia emerged from French colonial rule as a newly independent nation. At this pivotal moment, His Majesty King Norodom Sihanouk chose a policy of neutrality and non-alignment, rejecting military blocs and foreign domination. When the US and its allies sought to draw Cambodia into the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), he firmly refused, believing that alignment with Cold War military alliances would inevitably undermine Cambodia’s sovereignty and transform the country into a battlefield for greater powers.

This principled stance, however, placed Cambodia at odds with US strategic planners, as well as regional allies such as Thailand and South Vietnam, both deeply embedded in Cold War containment strategies. Cambodia’s neutrality was not treated as a legitimate sovereign choice, but rather as an obstacle. From that point onward, Cambodia became the target of political pressure, covert destabilisation and regional hostility.

Beginning in the late 1950s, foreign-backed efforts to undermine Cambodia’s leadership intensified. Exiled right-wing Cambodian groups received support from across the borders, particularly from Thailand and South Vietnam. Intelligence operations, propaganda campaigns and armed plots were directed at Phnom Penh. In 1959, a parcel bomb exploded inside the Royal Palace, killing palace aides and narrowly missing Prince Sihanouk himself — an event that reinforced widespread belief that foreign intelligence networks were actively pursuing regime change.

Throughout the 1960s, anti-neutrality elements were quietly encouraged and supported. Khmer Serei rebels received funding, training facilities were provided in neighbouring countries and Cambodian officers hostile to neutrality were cultivated as political instruments. The objective was clear: to remove Cambodia’s neutral leadership and convert the country into a pro-aligned military state within the broader Indochina conflict.

This long campaign culminated in March 1970, when General Lon Nol and Prince Sirik Matak overthrew Prince Sihanouk whilst he was abroad. The coup abruptly ended Cambodia’s neutrality and opened the country to massive foreign military involvement. Cambodia was drawn directly into the Vietnam War, subjected to extensive aerial bombardment and plunged into full-scale civil war. Rural areas were devastated, millions of civilians were displaced and state authority collapsed.

The social consequences were catastrophic. The destruction of villages, the loss of livelihoods and the breakdown of governance radicalised large segments of the population. In this environment of chaos and suffering, the Khmer Rouge — once a marginal force — expanded rapidly. The civil war culminated in their seizure of power in 1975, followed by one of the worst genocides of the twentieth century.

From 1975 to 1979, Cambodia endured mass executions, forced labour, starvation and the systematic destruction of society. Even after the fall of the Khmer Rouge, peace did not return. From 1979 through the 1990s, Cambodia remained trapped in conflict, international isolation, proxy warfare and economic collapse. Armed factions continued to fight, borders remained militarised and Cambodian civilians suffered long after the genocide had ended.

The historical truth often omitted is that Cambodia did not collapse because it lacked leadership or resilience, but because it refused to surrender its sovereignty. A genuinely neutral Cambodia was not permitted to exist in Cold War Southeast Asia. Regional actors — particularly Thailand — played critical roles as logistical hubs, intelligence partners and staging grounds for forces seeking to reshape Cambodia’s political direction.

The sequence of events is clear and continuous:

1954 neutrality → regional hostility → covert destabilisation → assassination attempts → the 1970 coup → civil war → genocide → prolonged post-1979 conflict.

These were not isolated incidents, but interconnected phases of a single historical process shaped by regional ambitions and global power politics.

The language of peace is always welcome. Yet history obliges some nations — especially Cambodia — to approach global initiatives with caution and a long memory. Neutrality was not chosen out of fear or indecision; it was chosen out of wisdom, realism and responsibility toward the Cambodian people.

Despite repeated efforts to remain outside great-power rivalry, Cambodia was ultimately drawn — against the will of its people — into a designated war. The consequences were devastating: violations of neutrality, secret military actions, loss of effective sovereignty, internal conflict, institutional collapse and one of the gravest human tragedies of the twentieth century. These are not abstract lessons; they are living memories carried quietly across generations.

For this reason, when new international groupings or peace frameworks emerge — particularly those linked, directly or indirectly, to major-power competition — it is natural for old fears to resurface. These concerns do not arise from hostility or mistrust, but from historical awareness that Cambodia has too often paid the price for decisions made by others.

Cambodia does not oppose peace. A nation that has endured such suffering understands its value more deeply than most. However, peace initiatives must be genuinely inclusive, non-aligned, and respectful of neutrality. Peace must never become a substitute for strategic pressure, political alignment or bloc politics.

If participation in any peace framework is truly voluntary, Cambodia’s long-standing tradition of neutrality should be preserved, allowing balanced and respectful relations with all sides. In simple human terms, Cambodia should remain free to call both sides “Mum and Dad”, without being forced to choose between them.

If participation were ever to become mandatory, it must be guided by clear principles: no military alignment, no security obligations, no foreign bases and no erosion of independent foreign policy. Any framework that weakens sovereignty or disregards historical experience risks repeating past mistakes under new terminology.

Cambodia’s neutrality is not passivity or isolation. It is a hard-earned survival strategy — shaped by history, suffering and resilience. The international community should recognise that Cambodia understands, perhaps better than many, what happens when small nations are drawn into rivalries they did not create.

True peace listens to history.

True peace respects neutrality.

True peace ensures that Cambodia will never again be forced into a war it does not want.

Tesh Chanthorn is a Cambodian citizen who longs for peace. The views and opinions expressed are his own.

-The Phnom Penh Post-