Burned or Bulldozed, a War Crime Is Still a War Crime

#opinion

Thailand’s First Army Region now claims it did not burn homes in Chouk Chey village in Banteay Meanchey province—only dismantled and demolished them. This semantic defense insults both the intelligence of the international community and the suffering of civilians whose lives were erased by military force.

Whether homes were torched or flattened by bulldozers, the act remains the same—deliberate destruction of civilian property by an occupying military force. International humanitarian law does not absolve an army because it chose excavators over fire.

The Thai military’s statement carefully avoids the real issue. The question is not how the houses were destroyed. The question is why Thai troops were destroying civilian homes at all on disputed territory during and after a ceasefire.

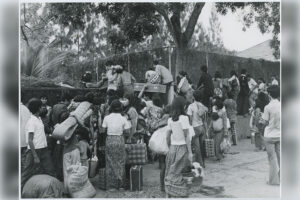

Thailand insists the videos circulating online were “not taken in Chouk Chey” and not even in Sa Kaeo province. Yet foreign journalists, independent observers, and displaced villagers have documented the same pattern repeatedly: civilian houses rendered uninhabitable, communities forcibly cleared, and physical “facts on the ground” imposed unilaterally by armed troops.

If the Thai army is confident in its claims, it should welcome independent international verification, not rely on closed internal reviews that conveniently absolve itself.

More troubling is the admission embedded in the denial itself. Thailand openly acknowledges that its troops demolished structures. These were not military installations. They were homes. Under the Geneva Conventions, the destruction of civilian property is prohibited unless absolutely required by military necessity. Thailand has offered no credible explanation of such necessity—only blanket denials and bureaucratic wordplay.

Demolition is not restraint. It is not legality. It is collective punishment by machinery.

This denial also collapses under basic logic. If Thailand claims the area is unquestionably its sovereign territory, why does it need to erase villages, dismantle homes, and remove civilians? Sovereignty does not require bulldozers. Occupation does.

Even more damning is the timing. These acts occurred after a truce meant to halt violence and protect civilians. Destroying homes under the cover of a ceasefire is not peacekeeping—it is territorial consolidation by force.

Cambodia does not accept faits accomplis created through intimidation, demolition, or military presence. Borders are defined by treaties, joint boundary mechanisms, and international law—not by containers, barbed wire, or the rubble of civilian homes.

Thailand may argue about fire versus demolition. History, however, will record something far simpler:

An army crossed into disputed land, destroyed civilian property, and then tried to redefine violence through technicalities.

The world should not be distracted by the method. The crime lies in the act—and the act is undeniable. Burned or bulldozed, injustice leaves the same ashes behind.

Roth Santepheap is a geopolitical analyst based in Phnom Penh. The views expressed are his own.