Fence, Maps and Silent Guns: What the Border Really Says About Us

#Opinion

Cambodia and Thailand have again found themselves staring at each other across an invisible line that never truly rests. On October 19, Thailand’s Foreign Ministry confirmed it would notify Cambodia of plans to build a border fence along what it described as the agreed sovereign boundary near Ban Nong Chan and Ban Nong Ya Kaew. Only hours earlier, Royal Thai Army spokesman Major General Winthai Suvaree declared those same areas to be Thai territory and insisted that no further review by the Joint Boundary Commission was necessary. Two statements, one government, and one message behind them both. Control of process is control of truth.

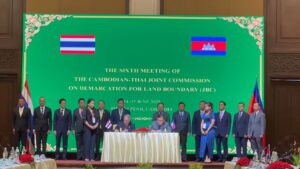

For more than a century, the 817 kilometre frontier between Cambodia and Thailand has carried the weight of history. The border was originally defined by the 1904 Convention between Siam and France and later reaffirmed by the 1907 treaty, but those lines on colonial maps were never fully settled. The Joint Boundary Commission, which last met in 2018, is now being revived in an attempt to formalise what the treaties left ambiguous. After the ceasefire of July 2025, brokered with assistance from Malaysia and the United States, many believed calm had finally returned. Instead, new mines appeared in already cleared zones, loudspeakers carried ghostlike sounds across the fields at night, and border families once again fled their farms. Reports verified by Reuters and The Guardian confirmed that the acoustic broadcasts continued for days after the ceasefire, prompting Cambodia’s Human Rights Commission to accuse Thailand of psychological warfare. In response, government spokesperson Pen Bona reminded Bangkok that any unilateral action in undelimited zones violates the international principle of non alteration of the status quo established by the United Nations Charter.

To Thailand’s civilian and military leadership, the border has become more than a line on a map; it is a performance of sovereignty for two different audiences. The Foreign Ministry presents a picture of consultation for international partners while the Army asserts unilateral control for domestic legitimacy. Thai commanders justify the fence as a protective measure for civilians against mines and encroachment, yet Cambodian officials view it as a pretext designed to fix political reality before the law can speak. This dual performance reflects Bangkok’s internal balance between the new coalition government and the armed forces that still hold decisive power. For the military, any appearance of concession risks backlash from nationalist constituencies. For the civilian administration, visible control reassures voters of stability. The fence serves both purposes. By appearing before any new delimitation, it becomes less an act of security and more a claim of authorship.

Cambodia, for its part, has chosen the harder path of patience. Officials continue to base every statement on the record of the 1904 and 1907 treaties, the 1 to 200000 map used by the International Court of Justice, and the seventy four recognised boundary markers registered with the United Nations. These are not symbols of nostalgia but instruments of consistency. They prove that sovereignty can be protected through law as firmly as through force. Cambodia’s decision to keep communication channels open with Bangkok is an act of confidence, not weakness. It recognises that restraint is a weapon of its own, one that gains strength with time and credibility. Yet even the strongest evidence must still compete with the power of imagery. A fence photographs better than a clause. A broadcast travels faster than a treaty.

Regional mediation may decide whether this renewed dialogue turns toward permanence or returns to the old cycle of flare and freeze. Malaysian diplomats coordinating the upcoming ASEAN Summit in Kuala Lumpur have indicated through internal working notes that both sides are expected to reaffirm the 2013 International Court of Justice implementation framework as part of what is being drafted as the Kuala Lumpur Accord. The initiative, supported by the United States and quietly observed by China, will test ASEAN’s ability to manage disputes within its own architecture. If the final document includes clauses on civilian protection, prisoner exchange, and joint mine monitoring, the region may see its first legally structured peace in decades. If those commitments are softened into general language about confidence building, the familiar pattern will return, with each side claiming progress while the ground remains contested. The border is fast becoming a test of ASEAN’s capacity to police its own peace architecture.

What is unfolding now is not a story of villains and victims but of systems and maturity. Both nations have changed since the violent clashes of 2011. The fact that negotiations now revolve around wording rather than weapons shows that the region has grown, even if the habits of spectacle remain. Yet every step toward process also reveals how much both nations still carry the ghosts of mistrust. Cambodia’s quiet legalism can only be sustained if met by Thailand’s equal restraint. When either side begins to use visibility as strategy, peace becomes its first casualty.

Behind the diplomatic theatre are ordinary lives. In O Bei Chorn, families say the silence after weeks of loudspeakers feels heavier than the noise itself. In Ban Nong Chan, the smell of burnt grass still hangs where a mine exploded last week. Children walk to school past warning signs printed in two languages. On the Thai side of the fence, villagers live with the same uncertainty, fearing both mines and misinformation. These people are the human measure of policy. They experience borders not as lines but as sounds, silences, and absences. When political arguments claim to protect them, they listen for what those promises actually deliver.

The next seventy two hours will be decisive. The Joint Boundary Commission meets in Chanthaburi on October 21 and 22 to finalise agenda language for the upcoming summit. Whether the minutes record the phrase agreed boundary or temporary works will decide more than semantics. Each word carries legal memory. Malaysia will host the Kuala Lumpur Accord days later, hoping to turn ceasefire into structure. If Cambodia can preserve clear language on undelimited zones and secure reference to independent monitoring, the agreement will carry moral weight. If the wording bends toward ambiguity, the pattern of symbolic peace will resume.

This is not only about land or markers. It is about who controls narrative and process, who owns the script of reconciliation, and who defines the future rules of sovereignty in our region. Fences, loudspeakers, and mines are symptoms of deeper habits; the belief that visibility equals power. Real peace demands the opposite, the confidence to restrain rather than to display. The first fence is always built out of words, and once those words harden into policy, they are harder to move than stone.

Ponley Reth is a Cambodian writer and commentator based in Phnom Penh. The views and opinions expressed are his own.

-Khmer Times-