Thai ceasefire narrative raises questions as ground reality points to territorial ambition

Thai forces have installed barbed wire and shipping containers on the ground, extending more than one kilometre into Cambodian territory. AKP

Thai forces have installed barbed wire and shipping containers on the ground, extending more than one kilometre into Cambodian territory. AKP

#National

Thailand’s insistence that it is strictly complying with the December 27 ceasefire agreement with Cambodia has drawn growing scrutiny, as conditions on the ground along the border tell a markedly different story.

In a January 12 statement, Thailand’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs rejected what it called “baseless allegations” that Thai forces are illegally occupying Cambodian territory, arguing that the maintenance of current troop positions after the ceasefire constitutes compliance with agreed de-escalation measures.

“Thailand, therefore, wishes to register its strong protest against Cambodia’s baseless allegations claiming Thailand is illegally occupying and conducting military operations across various areas in Cambodian territory after the ceasefire agreement was reached,” it said.

“The maintenance of current troop positions following the ceasefire constitutes direct compliance with agreed de-escalation measures that are clearly stipulated in Paragraph 2 of the Joint Statement. This cannot be misconstrued as territorial occupation,” it added.

Bangkok also warned that Cambodia’s claims risk undermining an environment conducive to peaceful dialogue.

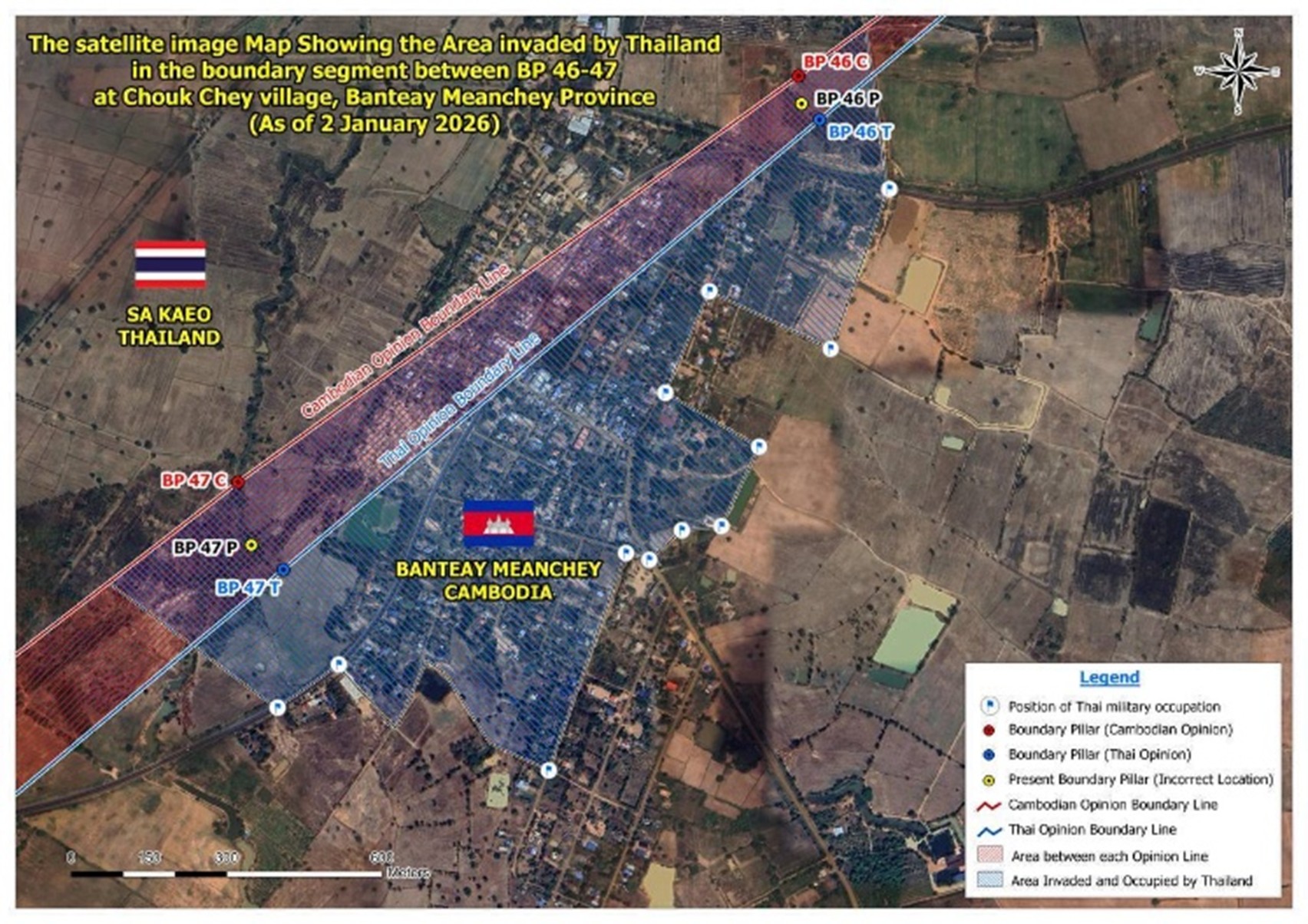

However, satellite imagery cited previously by Cambodian authorities and testimonies from affected communities, raise serious questions about whether Thailand’s position is rooted in de-escalation — or political manoeuvring to consolidate territorial control.

While Phnom Penh has not yet issued an official response to the Thai statement, facts on the ground remain unchanged: Thai troops continue to be present in multiple contested locations inside Cambodia, particularly in Banteay Meanchey, Pursat, Preah Vihear and Oddar Meanchey provinces.

In several areas, Thai forces have erected barbed wire, placed shipping containers, dug trenches and restricted civilian movement — actions that go beyond passive “maintenance of positions” and resemble the physical entrenchment of control.

Politics over process

Cambodia had proposed a special Cambodia-Thailand Joint Boundary Commission (JBC) meeting in Siem Reap as early as late December to hold talk during this January, to urgently address incidents on the ground and resume joint survey and demarcation work.

The State Secretariat of Border Affairs has announced that the special meeting of the JBC, initially scheduled for early January 2026 in Siem Reap, has been postponed at the request of the Thai side, citing the need to complete internal procedures.

Thailand’s statement places heavy emphasis on the Joint Boundary Commission (JBC) as the sole mechanism for resolving border issues, while simultaneously adding that it is not yet ready to resume JBC activities due to internal political procedures following its general election.

“Thailand is currently finalising internal procedures required which must follow the formation of the new Cabinet after the General Election, and will communicate the proposed date and draft agenda for the next JBC meeting to the Cambodian side in due course,” said the Thai foreign ministry.

However, it stated that Thailand urged Cambodia to promptly carry out remaining de-escalation measures under the Joint Statement, particularly humanitarian demining to protect civilians and survey teams.

Civilians caught in the middle

Along Cambodia’s north-western border, the ceasefire has not translated into a return to normal life.

As of January 11, an additional 5,754 displaced persons had returned to their homes. Therefore, out of a total of more than 640,000 displaced persons, approximately 480,000 displaced persons have returned to their homes.

“As a result, 161,472 displaced persons remain in displacement camps,” according to the Cambodian Ministry of Interior.

Some villages bear the scars of December’s fighting, with homes destroyed, unexploded shells left behind and residents prevented from returning due to security restrictions imposed by Thai troops.

For villagers, the debate over legal interpretations of the Joint Statement is abstract. What they see instead are barriers cutting through farmland, foreign armed soldiers controlling access to homes and lingering threats of violence.

These conditions undermine Thailand’s claim that its post-ceasefire actions are non-provocative.

Chouk Chey village chief Pen Rithy said on January 4 that the village, home to 807 families (3,022 people) has been surrounded by the Thai military, with 707 Cambodian families affected – over 87 per cent of the population.

“This illegal occupation of Cambodian territory is extremely serious,” said Rithy, adding that the villagers still have hope the government to settle this issue for them.

Prey Chan village in Ou Beichoan commune, O’Chrov district of Banteay Meanchey province, is home to about 270 families, or roughly 700 people.

Resident Si Soeuy, 62, said her home was destroyed by Thai forces. She was evacuated to Chan Si Monastery, which had been sheltering thousands of displaced people, forcing her family to flee and preventing their return due to ongoing security threats.

“Our houses are completely destroyed, and we don’t dare go back now. The Thais have surrounded us with barbed wire and are threatening to shoot if Cambodians come near,” she said.

-The Phnom Penh Post-