Cambodia Is Learning to Speak Peace in Its Own Accent

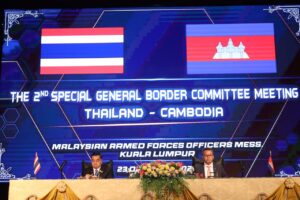

[The foreign ministers of Cambodia and Thailand met for talks in Malaysia last week, facilitated by the US and ASEAN chair Malaysia. Foreign ministry]

[The foreign ministers of Cambodia and Thailand met for talks in Malaysia last week, facilitated by the US and ASEAN chair Malaysia. Foreign ministry]

-Opinion-

There comes a moment when a nation no longer argues for its legitimacy; it simply writes it. After half a century of explaining itself to the world, Cambodia has reached that moment. This week, the country did not announce peace as an aspiration; it performed peace as authorship.

When foreign minister Prak Sokhonn stood before Malaysia, the US and Thailand, the words he used were not only diplomatic; they were curative. Every sentence in his statement carried the weight of a nation that once learned language through survival. The peace document he spoke of was less a treaty than a mirror, a reflection of how far Cambodia has moved from reaction to creation.

After months of border noise and rumour, the statement arrived as punctuation, not at the end of a conflict but at the beginning of maturity. To speak of peace after enduring accusations is not weakness; it is calibration. Cambodia has found a way to use tone as strategy. It no longer needs volume to be heard. For those who have lived through the noise, this calm feels unfamiliar, but it is ours now.

For decades, we defended ourselves in other people’s grammar. We responded to accusations, explained misunderstandings, absorbed misquotations. But today’s Cambodia drafts its own syntax of dignity.

When Sokhonn thanked Malaysia for its facilitation and recognised the role of President Trump and Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim as witnesses, it was not submission; it was choreography, an understanding that diplomacy too has rhythm. A small country was showing that peace can be engineered through discipline of tone, not display of might.

Yet this movement is not without friction. Along the border, villagers still report ghostlike sounds, roaring engines and eerie wails broadcast from loudspeakers, fragments of psychological warfare that disturb the night and unsettle the elderly. Children wake, mothers hush, soldiers listen.

Across the frontier, accusations of new landmines echo, injuries among Thai soldiers, claims of PMN-2s newly planted. Cambodia denies this, framing the danger as the lingering debris of old wars, not new aggression. The tension over mines remains a contested field of evidence, memory and legitimacy. In these human tremors lies the true cost of unfinished peace.

Beyond the conference halls, peace begins in the smallest rituals: border guards lowering their voices, farmers hearing silence instead of speakers, students scrolling through news without fear of what might break next. These are not metaphors; they are the quiet dividends of language done right.

Between the full ministerial statement and the condensed AKP release lies a method, a new national voice being trained. It learns to compress complexity without losing depth, to translate caution into calm, to build credibility from restraint. That is not theatre; it is the craft of sovereignty. When Cambodia says we want peace, it is no longer pleading. It is defining the standard of peace that others must learn to meet.

Peace requires two silences, ours and theirs. To speak calmly beside larger powers is not submission; it is strategy. Cambodia’s calm has become regional gravity, the quiet that others must orbit. Our neighbours may interpret this as politics, our critics as posture. But the truth is simpler: Cambodia has discovered that the real battleground is linguistic. To speak peace first is to own the frame of history.

This is the new accent of our foreign policy, quiet, deliberate, unafraid. The same cadence that once carried scars now carries structure. In every clause of Sokhonn’s statement, you can hear the country repairing itself, not through force or demand but through the steady rhythm of reason.

The next test of peace will not be at conferences but in ministries, classrooms and broadcasts that learn to speak with the same patience. Every generation must be taught that calm is not passivity; it is intelligence at rest.

Because peace is not a gift. It is a learned language. And this week, Cambodia spoke it fluently, in its own accent, for the first time.

Ponley Reth is a Cambodian writer and commentator based in Phnom Penh. The views and opinions expressed are his own.

-The Phnom Penh Post-